Sacré-Coeur 3 – BP 15177 CP 10700 Dakar Fann – SENEGAL.

+221 33 827 34 91 / +221 77 637 73 15

contact@timbuktu-institute.org

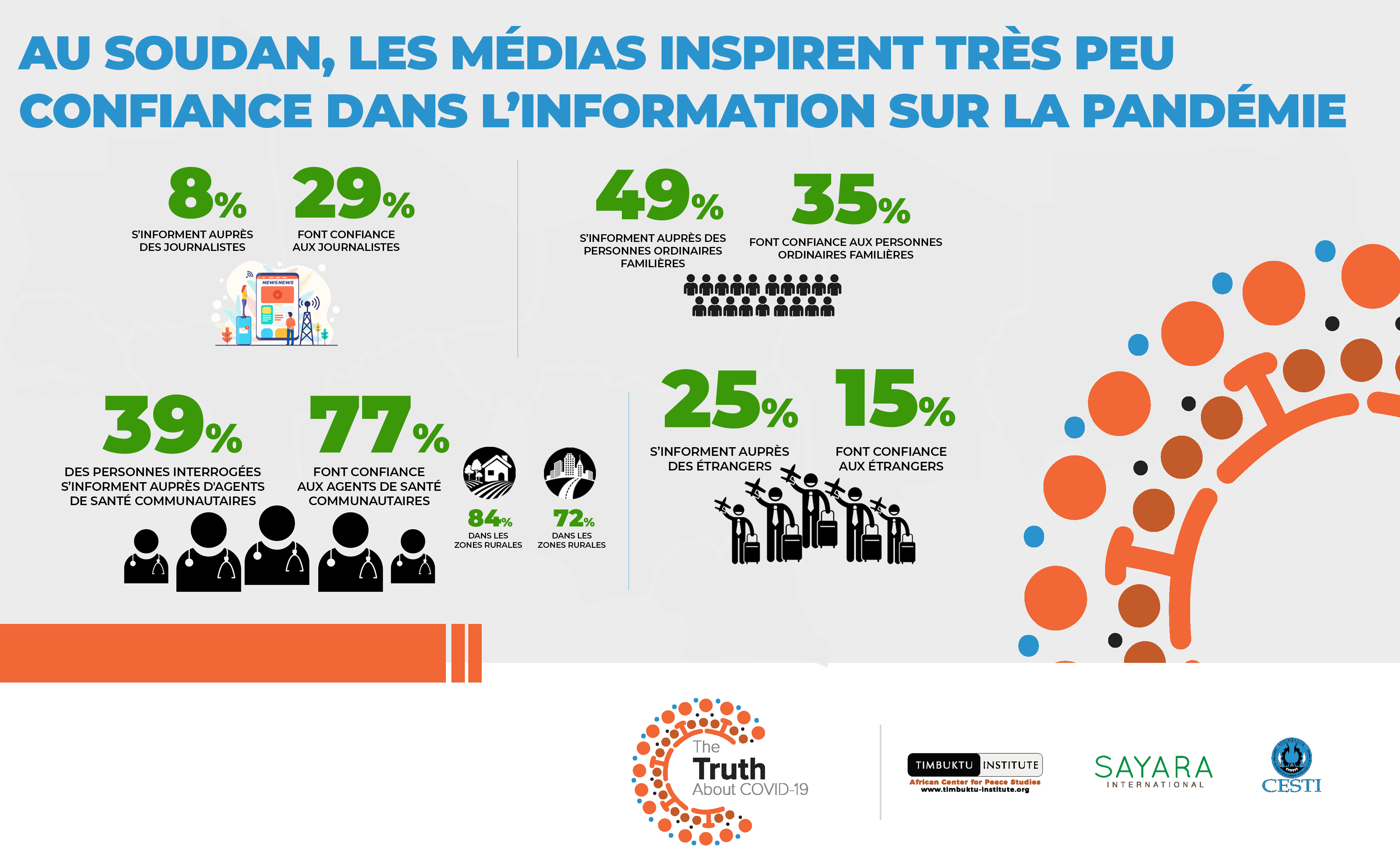

Quand il s’agit de s’informer sur la pandémie de COVID-19, les Soudanais font peu confiance aux médias. C’est ce que révèle une enquête menée par le Timbuktu Institute et Sayara International en décembre 2020, où seulement 8% des personnes interrogées considèrent les journalistes comme des sources crédibles.

Il y a au Soudan une véritable crise de confiance dans les médias. C’est une des conclusions de l’étude réalisée par le Timbuktu Institute et Sayara International, destinée à analyser les perceptions et comportements des populations de huit pays du Sahel face à la pandémie (Sénégal, Mauritanie, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Cameroun, Tchad et Soudan). D’après l’étude, seulement 29% des Soudanais interrogés font confiance aux journalistes, et ces derniers ne sont une source d’informations sur la COVID-19 que pour 8% des répondants.

Au Soudan, les populations traversent clairement une crise de confiance à l’égard des médias. Les proches de l’entourage sont une source d'information pour 49% des personnes interrogées, mais seulement 35% leur font confiance. En outre, les étrangers, fait pour le moins particulier, constituent une source d'informations sur la COVID-19 pour 25% des personnes interrogées, mais seulement 15% leur font confiance.

Les répondants ayant un niveau d'éducation du cycle primaire font également confiance à 69% aux leaders religieux et communautaires, 52% pour les personnes du secondaire. On note donc à ce niveau que les personnes les plus instruites ont moins tendance à faire confiance à leurs leaders communautaires. Par ailleurs, 39% des personnes interrogées obtiennent des informations sur la COVID-19 auprès d'agents de santé communautaires, de médecins ou de scientifiques et 77% d'entre elles leur font confiance. Cette confiance est plus élevée dans les zones rurales (84%) que dans les zones urbaines (72%).

Le cœur de la pandémie a été une période éprouvante pour les médias du monde entier. Entre la psychose générale et les fake news, la méfiance envers les médias s’est particulièrement accentuée. Le Soudan n’a pas échappé à cette situation. L’heure soudanaise est donc au travail pour recouvrer cette confiance perdue.

Max-Bill

Soumettez-nous une information, les journalistes du CESTI la vérifieront.

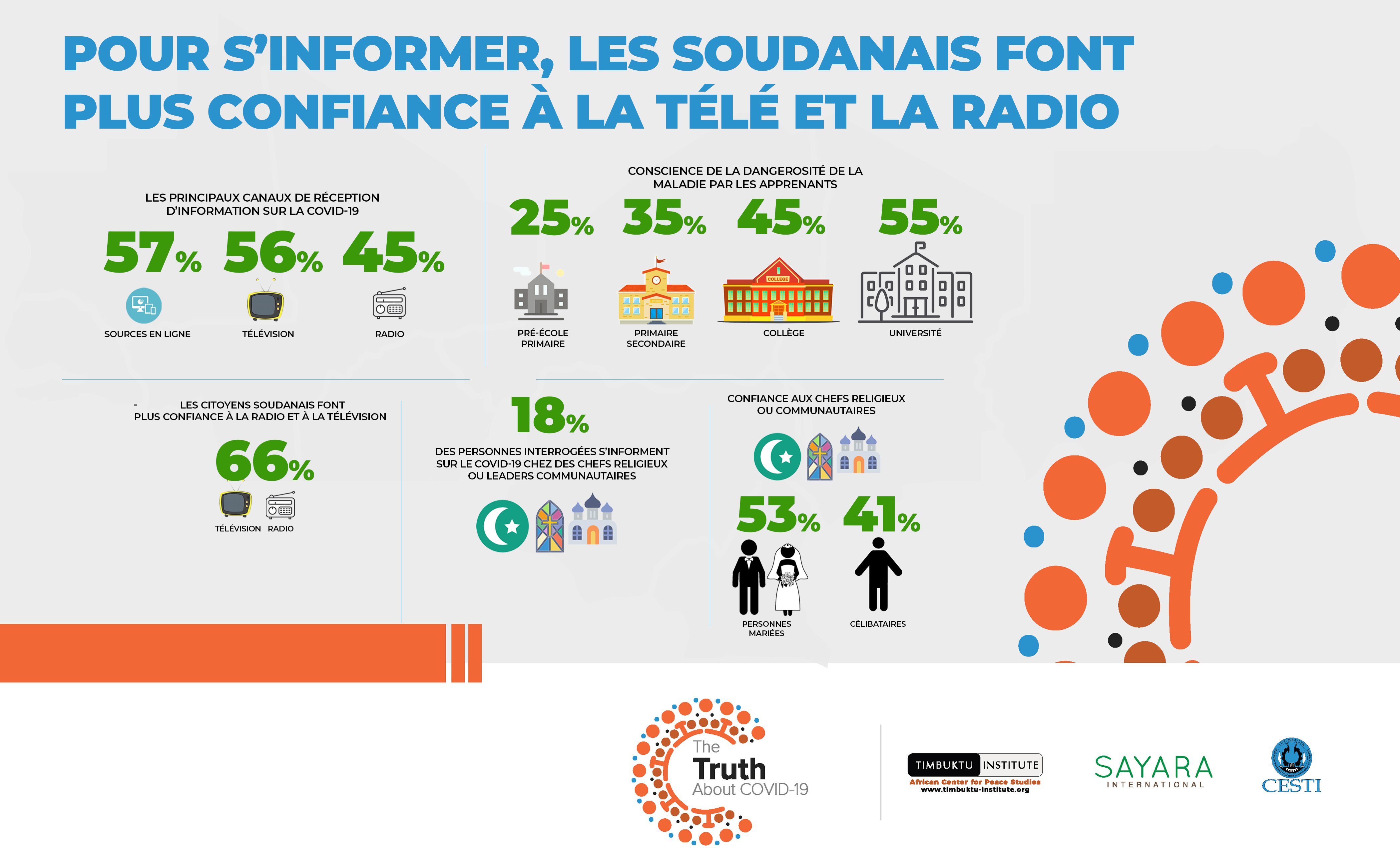

Menée en décembre 2020 en pleine pandémie de COVID-19, une étude réalisée par le Timbuktu Institute et Sayara International informe que les Soudanais font confiance aux canaux traditionnels que sont la télévision et la radio pour s’informer sur la COVID-19. Réalisée dans plusieurs pays du Sahel, cette étude se base sur un échantillon de plus de 4000 personnes

Selon les résultats de l’étude, les principaux canaux de réception sur la COVID-19 sont les sources en ligne (57%), la télévision (56%) et la radio (45%). Cela dit, les citoyens soudanais font, à part égale (66%), largement plus confiance à la radio et à la télévision. Les Soudanais accordent peu de confiance aux autres canaux d’information. Ainsi, les sources en ligne ont la confiance de 26% des Soudanais (29% pour les applications de messagerie) et, quant aux journaux, seulement 15% des personnes interrogées leur font confiance.

Les Soudanais font confiance à leurs chefs religieux

Les chefs religieux ou les leaders communautaires sont la source d'informations relatives à la COVID-19 pour seulement 18% des personnes interrogées au Soudan. Mais c’est 47% qui leur font confiance. Cette confiance est plus présente en zone rurale (51%) qu’en zone urbaine (43%). Les personnes mariées font davantage confiance aux chefs religieux ou communautaires (53%) que les célibataires (41%). Ce qui est compréhensible au regard de la place de l’institution matrimoniale dans un pays à 97% musulman. C'est la source auprès de laquelle les personnes interrogées ayant un niveau d'éducation inférieur au primaire obtiennent la plupart de leurs informations sur la COVID-19 (22%), et c'est la seule source à laquelle ce groupe fait confiance. En termes plus clairs, 59% d'entre elles font confiance aux leaders religieux/communautaires.

Somme toute, dans un contexte d’émoi suite à l’avènement de la COVID-19, les Soudanais, dans leur méfiance face aux médias, ont tout de même gardé le réflexe de s’informer sur les canaux traditionnels historiques, que représentent la télévision et la radio.

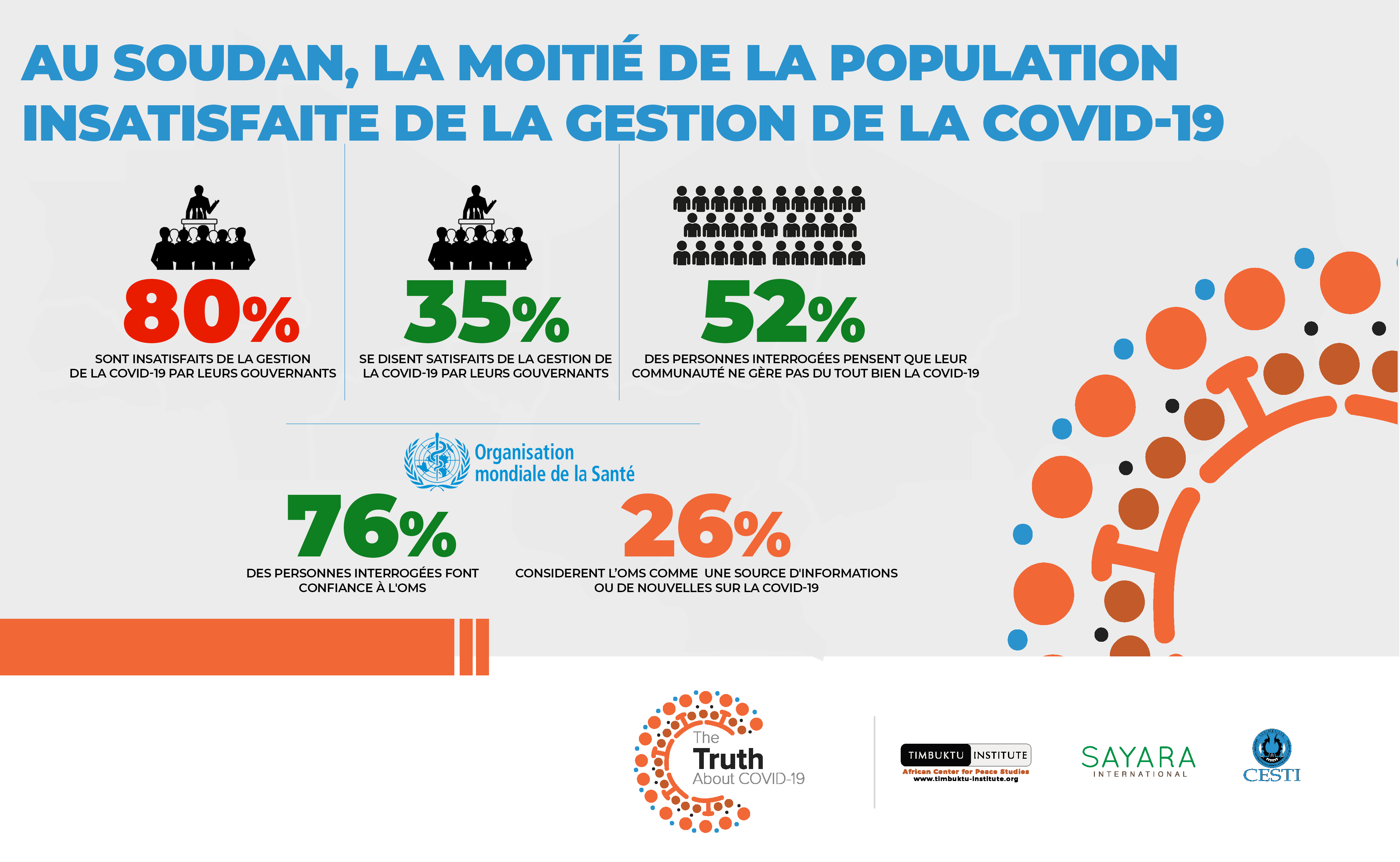

Selon une étude qui se propose d’analyser les comportements et perceptions des habitants du Sahel autour de la COVID-19, la moitié des Soudanais ne sont pas satisfaits de la réponse de leur gouvernement à la propagation de la COVID-19. Cette enquête a été menée par le Timbuktu Institute et Sayara International en décembre 2020.

Selon les résultats de cette étude réalisée sur un échantillon aléatoire de plus de 4000 personnes interrogées dans huit pays du Sahel (Sénégal, Mauritanie, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Cameroun, Tchad et Soudan), une écrasante majorité des Soudanais, soit 80%, sont insatisfaits de la gestion de la COVID-19 par leurs gouvernants.

D’après les entretiens conduits au Soudan, le sentiment d’insatisfaction des Soudanais serait dû à une campagne de sensibilisation à la COVID-19 menée par le gouvernement ayant utilisé des termes complexes et peu compréhensibles pour la majorité des Soudanais. De ce fait, 52% des personnes interrogées au Soudan pensent que leur communauté ne gère pas du tout bien la COVID-19, contre environ 20% dans le Bassin du Lac Tchad et dans le Sahara Occidental. « Les messages diffusés par le gouvernement pour les campagnes de sensibilisation à la COVID-19 n'ont pas atteint toutes les couches de la population. En fait, la terminologie utilisée était trop compliquée », selon l’une des personnes interrogées.

Seulement 35% des répondants se disent satisfaits de la réponse apportée par leur gouvernement, ce qui s’explique par la prise de mesures inadéquates. En outre, le système de santé soudanais est fragile et mal structuré, et le secteur médical est débordé en raison de la faible capacité générale des hôpitaux. Un état de fait accentué par la pandémie. Entre autres, le système de santé ne bénéficie pas d'un soutien financier suffisant ni de médicaments et d'équipements de protection individuelle (EPI).

Bien que 76 % des personnes interrogées font confiance à l'OMS, celle-ci n'est une source d'informations sur la COVID-19 que pour 26 % d'entre elles. En somme, même si une organisation comme l’OMS peut inspirer de manière générale une certaine confiance, les Soudanais ne se tournent pas systématiquement vers elles lorsqu’ils cherchent à s’informer. Dans un pays où la structure traditionnelle des rapports est encore présente, les populations vont plus vers leurs chefs religieux et communautaires.

Par: Max-Bill

Soumettez-nous une information, les journalistes du CESTI la vérifieront.

Certes, la situation qui a prévalu jusqu’ici en Tunisie, sous les responsabilités des islamistes du mouvement Ennahdha et de leurs alliés, ne pouvait pas durer; c’était une situation inconstitutionnelle et insupportable à plus d’un titre. Elle ne doit pas non plus être un prétexte pour imposer au pays un Etat d’exception qui peut déboucher sur l’instauration d’une dictature à l’instar de ce qui s’est produit en Egypte et partout où l’état d’exception a trop duré.

Par : M. Cherif Ferjani

Les problèmes dans lesquels s’est enlisée la Tunisie depuis des mois, voire des années, avec l’arrogance, le cynisme et l’incompétence des gouvernants et de l’ensemble de la classe politique, et avec l’aggravation des problèmes sanitaires, sociaux et économiques, la multiplication des explosions sociales qui ont culminé hier, dimanche 25 juillet 2021, jour anniversaire de la proclamation de la république, en 1957, et de l’assassinat jusqu’ici impuni du constituant Mohamed Brahmi, en 2013, ont rendu inévitables et prévisibles les décisions annoncées dans la soirée par le président Kaïs Saied : gel des activité et des prérogatives du parlement pour une durée de 30 jours, levée de l’immunité des députés et poursuites judiciaires contre tous ceux qui ont des affaires suspendues en raison de cette immunité, renvoi du chef du gouvernement Hichem Mechichi.

Désormais, le pouvoir exécutif sera assuré par le chef de l’Etat avec l’aide d’un chef de gouvernement qu’il désignera lui-même, le pouvoir judiciaire sera placé sous son autorité pour garantir l’ouverture de tous les dossiers bloqués, et le pouvoir s’exercera sur la base de décrets présidentiels jusqu’à nouvel ordre.

Le président affirme que les décisions annoncées avaient été précédées comme l’exige la Constitution, par la consultation du chef du gouvernement et du président du parlement et qu’il s’engage à ne rien faire en dehors de la légalité constitutionnelle.

De leur côté, Rached Ghannouchi, son parti et ses alliés parlent d’un coup d’Etat et affirment qu’ils vont défendre la légalité et la révolution contre ce coup de force. Ils refusent le gel des activités du parlement qu’ils déclarent en réunion ouverte jusqu’à la fin de l’état d’urgence.

Si les deux parties tiennent à leurs positions, le pays risque de sombrer dans une guerre civile dont l’issue est imprévisible.

Si rien n’empêche Kaïs Saied d’aller jusqu’au bout dans la réalisation de son projet annoncé depuis sa candidature à la présidence, ce sera la fin de la transition démocratique et le risque de voir se reproduire en Tunisie le scénario égyptien. Rappelons que Sissi avait profité du coup d’Etat rampant des Frères musulmans, pour prendre le pouvoir et instaurer une dictature pire que celles que le pays avait connues ; une dictature qui dure depuis 2013 et qui n’épargne aucune opposition politique ou civile.

Certes, la situation qui a prévalu jusqu’ici, sous les responsabilités des islamistes et de leurs alliés, ne pouvait pas durer; c’était une situation inconstitutionnelle et insupportable à plus d’un titre. Elle ne doit pas non plus être un prétexte pour imposer au pays un Etat d’exception qui peut déboucher sur l’instauration d’une dictature à l’instar de ce qui s’est produit en Egypte et partout où l’état d’exception a trop duré.

Si le gel des activités du parlement est prévu pour 30 jours, avec la levée de l’immunité et la poursuite en justice tous ceux qui ont des affaires, aucun délai n’est annoncé pour la situation d’exception qui doit durer jusqu’à la fin des causes qui y avaient conduit, selon les termes du décret présidentiel promulgué dans la foulée du discours du chef de l’Etat. Rien ne garantit que cette situation ne durera pas au-delà de ce qui pourrait la rendre irréversible en considérant que les causes des décisions prises n’ont pas disparu.

Face aux deux risques auxquels le pays est exposé, les forces démocratiques et la société civile doivent se mobiliser et peser de toutes leurs forces pour fermer la porte à ces deux scénarios catastrophiques – la guerre civile et l’instauration d’une dictature – et exiger une feuille de route claire pour la sortie de l’état d’exception et pour l’organisation dans les meilleurs délais d’élections à même de donner aux pays des institutions démocratiques capables de gérer ses affaires et de la sortir de la crise dans laquelle il s’est enlisé depuis des années.

Les forces démocratiques et la société civile doivent également obtenir la tenue immédiate d’un vrai dialogue national dont émergeront des institutions provisoires appelées à superviser les prochaines élections et la refonte du contrat social de façon à sortir le pays d’une crise qui dure depuis au moins 10 ans.

Par : M. Cherif Ferjani président du haut conseil scientifique de Timbuktu Institute, African Center for Peace Studies.

Au Mali, le Premier ministre Choguel Maïga a appelé la population à une «union sacrée» après la tentative d’assassinat contre le Président de la transition, le colonel Assimi Goïta. Minimisé par ce dernier, cet attentat est plutôt synonyme d’un climat politique toujours «tendu» dans le pays selon des observateurs joints par Sputnik.

«Une action isolée», c’est ainsi que le Président de la transition malienne, le colonel Assimi Goïta, a qualifié la tentative d’attaque au couteau contre sa personne le jour de l’Aïd al-Adha, la fête musulmane qui a été célébrée le 20 juillet.

Le colonel Goïta s’était déplacé à la grande mosquée de Bamako ce jour-là pour sa première grande prière de circonstance en tant que Président, quand deux hommes l’ont attaqué, l’un d’eux étant armé d’un couteau. Les deux assaillants ont été arrêtés, mais leur identité de même que le mobile de leur acte ne sont pas encore connus. Une enquête a été ouverte.

L’air rassurant affiché par le Président de la transition malienne a contrasté avec l’attitude du Premier ministre, Choguel Maïga, qui s’est montré plutôt inquiet.

Intervenant le jour même sur la télévision publique malienne au JT de 20h, il a appelé les Maliens à une «union sacrée» autour des autorités de la transition, «pour prendre leurs destins en main».

«Aujourd’hui, plus que jamais, tout ce qui peut nous diviser doit être évité. Aucune considération d’ordre politique, d’ordre religieux, d’ordre régionaliste, d’ordre ethnique ne doit diviser les Maliens», a-t-il affirmé.

Cela pourrait être «l’heure de dépasser toutes les divergences qui existent actuellement entre les différents courants politiques», affirme à Sputnik le docteur Moulaye Hassan, enseignant-chercheur à l’université Abdou-Moumouni de Niamey et chef du programme Lutte contre la radicalisation et l’extrémisme violent au Centre d’études stratégiques et de sécurité du Niger.

D’après cet analyste, les autorités maliennes pourront saisir l’occasion de cette tentative d’assassinat «pour chercher un véritable consensus autour de la transition telle qu’elle est actuellement menée au Mali».

«Le Président actuel est loin de faire l’unanimité, aussi bien à l’intérieur du pays, qu’à l’extérieur. Beaucoup préfèrent le retour du pouvoir aux civils, car ils craignent que l’exemple malien ne soit dupliqué ailleurs en Afrique de l’Ouest», explique-t-il.

Bakary Sambe, directeur du think tank Timbuktu Institute basé à Dakar, reconnaît lui aussi que «le système politique malien est assez divisé et est en forte demande de réconciliation».

À titre d’exemple, il cite «le maintien en résidence surveillée des anciennes autorités de transitions déchues par la junte au pouvoir, c’est-à-dire Bah N’Daw, l’ex-Président de la transition, et Moctar Ouane, l’ex-Premier ministre».

«IL Y A UN FORT BESOIN QUE LES AUTORITÉS DE TRANSITION RASSURENT DAVANTAGE SUR L’ISSUE FAVORABLE DE LA TRANSITION», PLAIDE BAKARY SAMBE.

Cela pourrait passer par une «recomposition de l’équipe gouvernementale actuelle dominée par des militaires qui sont aux postes-clés». Une «prédominance» qu’il assimile à «un véritable problème».

Auteur de deux putschs en moins d’un an, le colonel Assimi Goïta est au pouvoir au Mali depuis sa prestation de serment devant la cour suprême le 7 juin dernier. Son premier coup d’État, qui remonte au mois d’août 2020, a eu raison du pouvoir d’Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. Le deuxième putsch a été perpétré en mai 2021 contre les autorités de la (première) transition mise en place après la chute d’IBK, et ce nonobstant l’opposition de la communauté internationale. Il est attendu que le pouvoir soit rendu aux civils aux termes d’élections prévues le 27 février 2022.

Au Soudan, compter sur le respect de la distanciation sociale dans la lutte contre la COVID-19 se révèle une entreprise difficile. En effet, la sociologie soudanaise montre un fort ancrage communautaire des habitants, selon une enquête de Timbuktu Institute et Sayara International. L’objectif de cette enquête a été d’analyser les perceptions des populations du Sahel des informations circulant sur la COVID-19.

Cette enquête a été réalisée en décembre 2020 dans huit pays du Sahel : Sénégal, Mauritanie, Mali, Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Niger, Tchad, et Soudan. Avec un échantillon hautement représentatif de plus de 4000 répondants à un questionnaire quantitatif et plus de 30 entretiens qualitatifs, elle a été menée par 80 enquêteurs et 7 superviseurs locaux. L’échantillonnage probabiliste et aléatoire a donné à chaque individu de la population cible la chance d’être interrogé. Quatre strates homogènes (l’âge, le sexe, le niveau d’éducation, et le milieu de résidence [rural/urbain]) ont permis de catégoriser cette cible. Évaluer les pratiques des populations sahéliennes envers la COVID-19 a été l’un des objectifs de cette étude.

A défaut de pouvoir faire appliquer la distanciation sociale, prioriser le lavage des mains et le port du masque

Au Soudan, la distanciation physique ne devrait pas être mise en avant dans les campagnes de prévention. En effet, il est impossible pour la majorité des Soudanais de la mettre en œuvre. Ainsi, seulement 20% des répondants soudanais respectent toujours et souvent la distance d’au moins un mètre avec des personnes qui ne font pas partie de leur ménage. 44% respectent parfois et rarement cette distance. Enfin, ils sont 33% ne la respectant jamais. Cela pourrait s'expliquer par le fait que la majorité des Soudanais vivent dans des maisons familiales, où les membres de la famille nucléaire et élargie cohabitent. De plus, il existe au Soudan une grande proportion de très petites maisons dans les zones les plus pauvres (à l'intérieur des villes, dans les périurbains et dans les zones rurales).

Le succès de la lutte contre la COVID-19 au Soudan doit donc aussi passer par la consolidation des autres pratiques de prévention, comme le lavage des mains. 43% des Soudanais disent se laver fréquemment les mains pour contrer le virus, 62% des personnes interrogées savent que se laver les mains avec du savon aide à prévenir la propagation de la maladie, et 63% se sont lavé les mains régulièrement au cours de la semaine précédant cette enquête.

Le port du masque est aussi l’un des moyens de lutte contre la propagation de la COVID-19 qui doit être invoqué au Soudan. 72% des Soudanais interrogés approuvent cette mesure. Cependant, seuls 17% de Soudanais ont couvert leurs bouches lorsqu'ils ont toussé ou éternué au cours de la dernière semaine du déroulé de l’enquête.

La vaccination, une mesure plébiscitée

Les Soudanais sont plus favorables à la vaccination que dans les autres pays du Sahel. En effet, 75% sont favorables contre seulement 18% qui ne veulent pas du tout se faire vacciner.

Par: Max-Bill

Soumettez-nous une information, les journalistes du CESTI la vérifieront.

Ce nouvel ouvrage de l'Inspecteur principal des Douanes, Amadou Tidiane Cissé, vient en son heure pour partager aussi bien ses interrogations que ses pistes de réflexions prospectives sur la transnationalité du phénomène terroriste au Sahel. Son intitulé complet "Terrorisme: La fin des frontières ? Nouveaux enjeux de la coopération douanière en matière de sécurité au Sahel" (Editions Harmattan, Juillet 2021) nous plonge au coeur des récentes dynamiques sécuritaires dans la région où tous les pays peuvent devenir soient terrain d'opération ou zones de repli stratégique pour des groupes terroristes qui, au même titre que la globalisation des échanges économiques, ont, eux-aussi, depuis longtemps, aboli les frontières. Sans nul doute que le soldat de l'économie a aussi répondu au devoir patriotique d'instruire et de partage d'expériences pour consolider le rôle de la douane dans cette guerre asymétrique.

Par souci de pédagogie, au fil de cet ouvrage de 242 pages, sur un sujet éminemment complexe et sensible, Amadou Tidiane Cissé nous invite, progressivement, à revisiter les dernières évolutions régionales dans un style accessible alliant, en enquêteur chevronné, souci de précision et rigueur dans le croisement des sources. En parcourant, cet ouvrage qui vient à son heure, les spécialistes ou experts pourraient avoir l’impression d’un effort de description de situations et de mécanismes auxquels ils seraient familiers (groupes terroristes, acteurs et réseaux), mais le véritable apport de Amadou Tidiane Cissé est, surtout, d’avoir jeté un regard nouveau, parfois surprenant, sur un phénomène lisible sous plusieurs angles.

Le regard méticuleux du douanier pouvant aller au-delà des horizons et des frontières que nous fixent l’habitude et la fausse impression de maîtrise d’une réalité aussi changeante, complexe qu’évolutive a permis à l’auteur de nous guider dans l’univers sahélien des menaces asymétriques auxquelles seule une approche transdisciplinaire permettrait de faire dûment face.

Traitant de la question « djihadiste » au Sahel en passant en revue les différents acteurs (nébuleuses, groupes d’autodéfense), Amadou Tidiane Cissé a pu revenir sur les sources internes comme externes de financement du terrorisme avec le regard de l’enquêteur qui élargit les perspectives. L’analyse qu’il fait de l’origine des armes en retraçant les circuits renseigne sur l’étendue d’une culture douanière ouverte sur les dimensions sécuritaires au point de brosser une analyse exhaustive des modes opératoires faisant de cet ouvrage, un outil précieux aussi bien pour les chercheurs que les praticiens.

La maîtrise incontestée des instruments juridiques régionaux et internationaux décelée à travers leur approche comparative et complémentaire a certainement permis à l’auteur de faire constamment le lien entre les principes généraux, la palette des outils existants et les diverses contraintes du terrain et des réalités avec lesquelles l’administration douanière est amenée à composer.

En plus d’avoir sciemment permis le croisement des méthodologies d’analyses invitant à une désormais inévitable interdisciplinarité dans l’approche du fait terrorisme dans le Sahel, l’ouvrage de Amadou Tidiane Cissé est une courageuse invite à une certaine mitigation des paradigmes du tout-sécuritaire face à la mesure nécessaire entre gestion des urgences sécuritaires et enjeux de la prévention et de la prospective.

En parcourant cet ouvrage, même s’il ne faudrait pas totalement donner raison à un certain Frédéric Dard qui soutenait dans Les aventures du commissaire San Antonio qu’ « il n’y a que les douaniers qui sachent formuler des questions », il ne serait pas étonnant que certains lecteurs en arrivent à accorder, in fine, à Amadou Tidiane Cissé, la prouesse de nous instruire tout en nous questionnant.

Il est clair qu’au-delà des questionnements légitimes sur la viabilité de nos systèmes de sécurité face aux menaces émergentes et du rôle constructif de la douane dans la prévention et la lutte contre le terrorisme, de sérieuses pistes sont déjà dessinées quant à la pertinence d’une meilleure coopération entre les Etats de la région et les administrations douanières.

Par ailleurs, en refermant cet ouvrage, il devient évident pour les acteurs et observateurs que les défis posés par le terrorisme et l’ensemble des menaces sécuritaires requièrent, plus que jamais, une sérieuse mutualisation des efforts et des compétences au sein des Etats et entre eux de même qu’ils rendent, désormais, caduques toute forme d’exclusivité disciplinaire ou de cloisonnement des spécialités.

Par ce livre, Amadou Tidiane Cissé offre aux novices une pure délectation intellectuelle en termes de vulgarisation, une boîte à outils opérationnels pour les professionnels de la sécurité mais aussi une source d'inspiration pour les pouvoirs publics de la région confrontés à la gestion des urgences sécuritaires et la montée des périls dans une région en pleine mutation.

Par Bakary Sambe

Directeur du Timbuktu Institute