Sacré-Coeur 3 – BP 15177 CP 10700 Dakar Fann – SENEGAL.

+221 33 827 34 91 / +221 77 637 73 15

contact@timbuktu-institute.org

Sacré-Coeur 3 – BP 15177 CP 10700 Dakar Fann – SENEGAL. +221 33 827 34 91 / +221 77 637 73 15

contact@timbuktu-institute.org

Présente en Afrique depuis l’ère post-indépendance et plus intensivement à partir des années 90, le Japon cherche depuis lors à édifier un partenariat de choix avec les pays africains. C’est ce qui explique la création en 2003, de la JICA (Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale), sur les cendres de l’ancien organisme de coopération du même nom. Dans la récente étude menée par le Timbuktu Institute sur les perceptions locales des coopérations sécuritaires au Sahel et en Afrique de l’Ouest et qui a couvert la Côte d’Ivoire, le Niger, le Sénégal et le Togo, les perceptions sur la JICA laissent entrevoir un certain déficit de communication et une méconnaissance de son action. L’agence japonaise semble pâtir à la fois d’un défaut de visibilité et d’une méconnaissance de son action.

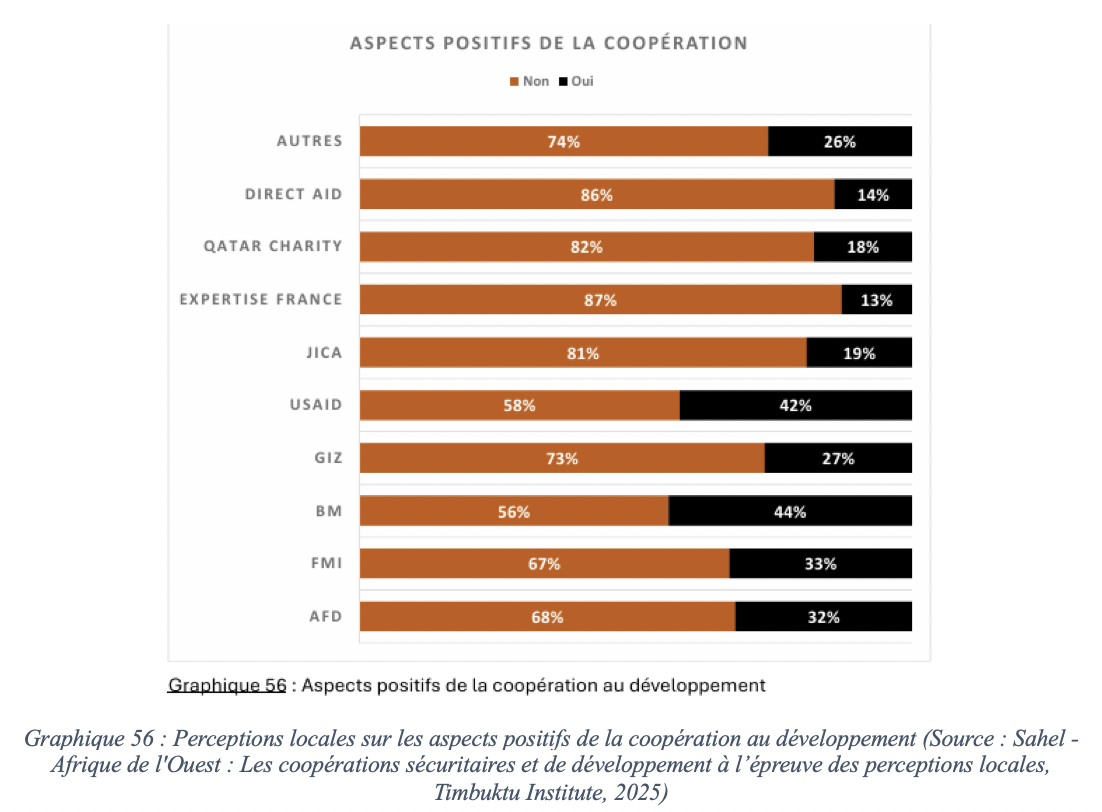

D’une manière générale, les résultats globaux du graphique ci-dessous, montrent que l’écrasante majorité des personnes interrogées ne voient pas d’aspects positifs de cette coopération au développement. Concernant la JICA (Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale), elle est l’une des institutions bénéficiant le moins de réponses positives (19 %) quant à sa politique centrale, loin derrière par exemple les traditionnels partenaires tels que l’USAID (42%), du FMI (33%) et de l’AFD (32%). Née le 1er octobre 2003, la JICA actuelle est le fruit d’un remodelage de l’ancien organisme semi-gouvernemental fondé en 1974, portant le même acronyme. Même si la coopération entre l’Afrique et le Japon n’est pas aussi importante qu’avec les partenaires occidentaux, elle reste bien dynamique. En témoigne, la Conférence internationale de Tokyo sur le développement de l'Afrique (TICAD) dont la première édition a lieu en 1993. Toutefois, les résultats de l’étude laissent à penser que la coopération entre l’Afrique et Japon semble méconnue.

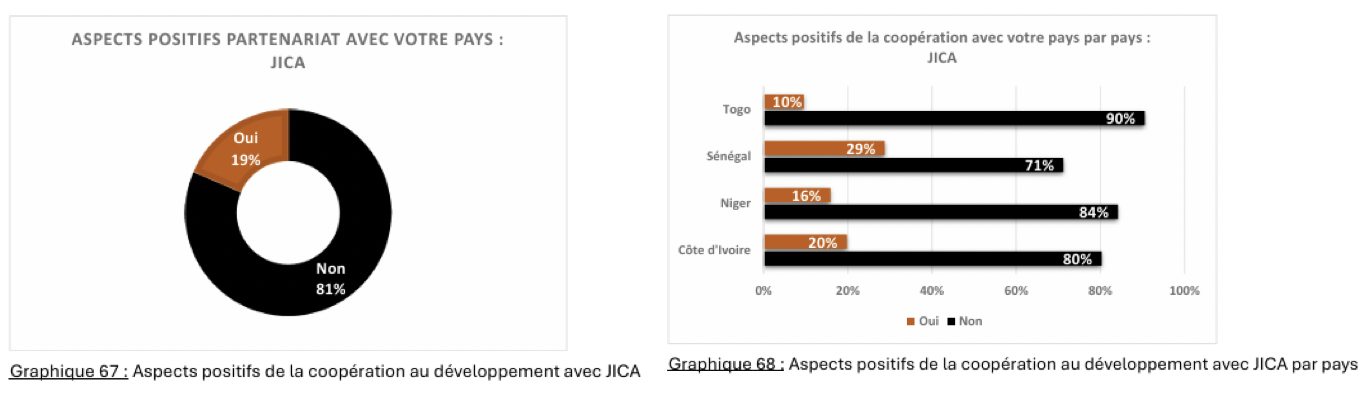

Par ailleurs, une grande majorité (81%), déclare ne pas connaître les aspects positifs de la coopération de la JICA avec leur pays (graphique 67). Ce résultat semble plus s’agir d’une méconnaissance que d’un jugement négatif sur les activités de la JICA. Pourtant, l’agence japonaise accompagne nombre d’États africains dans les domaines de l’éducation, la santé, l’agriculture entre autres à travers ses programmes et projets, en l’occurrence ces dernières années. Au Togo, les résultats apparaissent plus inquiétants ; 90% ont apporté une réponse négative à cette question sur les aspects positifs du partenariat avec cette agence japonaise de coopération (graphique 68).

Cet article est une version reprise et adaptée de certaines conclusions du rapport intitulé « Sahel - Afrique de l'Ouest : Les coopérations sécuritaires et de développement à l’épreuve des perceptions locales », publié par le Timbuktu Institute, le 16 janvier 2025.

Source : Sahel weather January 2025

Download the full Sahel weather report

In Guinea, the deadline for political parties to reorganize expired at the end of January. In a report published in October 2024, the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, after assessing 211 political parties to "clean up the country's political scene", dissolved 53 of them and placed around 100 "under observation", giving them three months to comply with the law. This measure prompted the political parties concerned, such as the Bloc Libéral (BL), to comply with the law. For its part, the Union des Forces Démocratiques de Guinée (UFDG) has officially convened an extraordinary national congress in Conakry in April 2025, as the authorities' report criticized it for not having renewed its governing bodies for some time. However, the Rassemblement du peuple Guinéen (RPG) is slow to comply with the ministerial authority's demands. The party's spokesman, questioned about the measures to be taken following the Ministry's report, asserts that the "information requested by the authorities has been provided by the RPG". As for the Congress, the delegate maintains that it is "the exclusive responsibility of the party".

The measures taken by Guinea's transitional authorities to streamline the country's political parties are seen by many as a multi-faceted pressure tactic on political players and human rights defenders in the run-up to the upcoming general elections. These restrictions on the political class, the media and civil society have been denounced in a United Nations report. The report notes a "growing and worrying erosion of social cohesion in Guinea", a "deterioration of democratic space and a narrowing of civic space and the rule of law". The UN experts also raised concerns about "the lack of clarity on the timetable for a return to constitutional order", "the lack of consensus around the new Constitution" and the "potential participation of transition leaders in a future presidential election".

As far as elections are concerned, and in particular the presidential election, it's all a blur. While the transition period negotiated with the international community in the wake of the 2021 coup d'état came to an end on December 31, the dates put forward for the return to constitutional order are multiplying and contradicting each other. In his New speechYear's , the President of the Transition declared that "2025 will be a crucial electoral year to complete the return to constitutional order" and that "a date for a referendum to adopt a new constitution will be announced within the next three months". This announced date was contradicted by the government spokesman, who in turn announced that the referendum held constitutional would be "at the end of the first half of the year", before adding in front of the press that "it would be impossible to hold all the elections in 2025", whereas the Minister of Foreign Affairs had assured us at the end of the year that "all the elections would be held this year".

Source : Météo Sahel Janvier 2025

Télécharger l'intégralité de la Météo Sahel

En Guinée, le délai accordé aux partis politiques pour leur réorganisation a expiré ce fin janvier. Dans un rapport publié en Octobre 2024, le ministère de l’Administration du Territoire et de la Décentralisation, après avoir évalué 211 partis politiques pour « assainir l’échiquier politique du pays », en avait dissout 53 partis et placé une centaine « sous observation », leur accordant trois mois pour se conformer à la loi. Cette mesure a poussé les partis politiques concernés à se mettre en règle à l’image du Bloc Libéral (BL). De son côté, l’Union des Forces Démocratiques de Guinée (UFDG) a officiellement convoqué un Congrès national extraordinaire à Conakry en avril 2025, car le rapport des autorités lui reprochait de n’avoir pas renouvelé ses instances depuis un certain temps. Cependant, le Rassemblement du peuple Guinéen (RPG), tarde à se conformer aux exigences de l’autorité ministérielle. Le porte-parole du parti, interrogé sur les mesures à prendre après le rapport du Ministère, affirme que les « informations demandées par les autorités ont été fournies par le RPG ». S’agissant du Congrès, le délégué soutient qu’il « relève exclusivement du parti ».

Ces mesures prises par les autorités de la transition, en Guinée, pour rationaliser les partis politiques, sont perçues par beaucoup d’acteurs comme un coup de pression qui revêt plusieurs formes sur les acteurs de la scène politique et les défenseurs des droits de l’homme, en prélude des élections générales à venir. D’ailleurs, ces restrictions visant la classe politique, les médias et la société civile, sont dénoncées dans un rapport des Nations Unis. Le rapport fait état d’un « effritement grandissant et inquiétant de la cohésion sociale en Guinée », d’une « détérioration de l’espace démocratique et un rétrécissement de l’espace civique et de l’État de droit ». Les experts de l’ONU ont aussi soulevé des préoccupations concernant « le manque de clarté sur le calendrier de retour à l’ordre constitutionnel », « l’absence de consensus autour de la nouvelle Constitution » et la « participation potentielle des dirigeants de la transition à une future élection présidentielle ».

Concernant les élections et particulièrement l’élection présidentielle, c’est le flou absolu. Alors que la période de transition négociée avec la communauté internationale, au lendemain du coup d'État de 2021 est arrivée à terme le 31 décembre passé, les dates avancées pour le retour à l’ordre constitutionnel se multiplient et se contredisent. Lors de son discours de Nouvel An, le Président de la transition avait déclaré que « l’année 2025, sera une année électorale cruciale pour parachever le retour à l’ordre constitutionnel » et « une date pour un référendum pour l’adoption d’une nouvelle Constitution serait annoncée dans les trois prochains mois ». Cette date annoncée est contredite par le porte-parole du gouvernement, qui à son tour, annonce la tenue du référendum constitutionnel « à la fin du premier semestre de l’année » avant de renchérir devant la presse « qu’il serait impossible de réaliser toutes les élections en 2025 », alors que le Ministre des Affaires Étrangères assurait en fin d’année que « toutes les élections se tiendraient en cette année ».

Source : Sahel weather January 2025

Download the full Sahel weather report

In Côte d'Ivoire, the candidacy of the current president continues to cause controversy. Indeed, Alassane Ouattara continues to maintain the vagueness surrounding his participation in the forthcoming elections. With nine months to go before the presidential election, he is still in a state of pendulum; on January 9, he stated that he had not yet taken a decision on his candidacy. Nevertheless, on January 9, 2025, he declared that he was "eager to continue serving" his country, while assuring that he had not yet made up his mind whether to run for a fourth term in the October 2025 presidential election. In any case, for his supporters, there is no plan B. The only good plan is plan A, like Alassane.

For his part, will Guillaume Soro stand in the October 2025 elections? His candidacy remains an equation with several unknowns to be resolved, given that the former rebel leader is still under an international arrest warrant and must benefit from an amnesty in order to run. It should be remembered that he announced his candidacy via an online meeting, as he was forced into exile. His dream of presiding over the country's destiny is increasingly shattered, given that the chances of Alassane Ouattara granting him amnesty are very slim. Meanwhile, on January 15, the Court of Appeal upheld the two-year prison sentences handed down to two of his lieutenants. These were two executives of his movement, Générations et peuples solidaires (GPS), arrested for "illegally maintaining a political party" and "undermining public order".

At the same time, the case of Laurent Gbagbo has also attracted public attention. He has been pardoned by the public authorities, but this does not erase the heavy charges against him, preventing him from being reinstated on the electoral roll. The same fate awaits Charles Blé Goudé, who still has the sword of Damocles hanging over his head from Lady Justice, preventing him from taking part in the next presidential election. The fratricidal duel between Houphouët's heirs is also still on the agenda. Indeed, Billon still maintains his "rebel" candidacy against the party's decision to invest businessman Tidjane Thiam. To resolve these nagging problems surrounding the electoral issue, some voices are calling for dialogue between the parties involved. The government, for its part, does not seem to agree with this proposal, since, according to the authorities, all these issues have already been discussed at previous national dialogues. On January 8, the government spokesman pointed out that the previous editions "enabled us to review all the concerns".

Diplomatic tensions with Burkina Faso continue to dominate the headlines. The diplomats recalled by Captain Traoré finally left Abidjan, further aggravating the situation. This strong action by the leaders of the two countries further complicates their bilateral relations. As a reminder, these conflicts have always existed between the two states under Houphouët and Sankara.

On another note, the beginning of 2025 marks a decisive turning point in security cooperation between Paris and Abidjan. How can we analyze this situation when we know that Côte d'Ivoire was once a staunch ally of the former colonizer? It should be noted that the French are not leaving Côte d'Ivoire altogether, as France is planning not a total withdrawal but a reduction in its armed presence, cutting the number of soldiers in the country from 2,200 to 600 as part of what it calls the "redeployment" of its military posture.

Source : Météo Sahel Janvier 2025

Télécharger l'intégralité de la Météo Sahel

En Côte d’Ivoire, la candidature de l’actuel président continue de semer la polémique. En effet, Alassane Ouattara continue toujours de maintenir le flou autour de sa participation aux prochaines joutes électorales. A neuf mois de la présidentielle, il est encore dans une position de pendule; le 9 janvier dernier, il a affirmé n’avoir pas encore pris de décision à propos de sa candidature. Néanmoins, il a déclaré, ce 9 janvier 2025, être « désireux de continuer de servir » son pays, tout en assurant ne pas avoir pris de décision au sujet de sa candidature à un quatrième mandat à la présidentielle d'octobre 2025. En tout cas, pour ses souteneurs, il n’y a pas de plan B. Le seul plan qui vaille, c’est le plan A comme Alassane.

De son côté, Guillaume Soro va-t-il se présenter à ces élections d’octobre 2025 ? Sa candidature demeure cette équation à plusieurs inconnues à résoudre vu que l’ancien chef rebelle est toujours sous le coup d’un mandat d’arrêt international et doit bénéficier d’une amnistie pour se présenter. Rappelons qu’il avait annoncé sa candidature à travers un meeting online car contraint par les liens de l’exil. Son rêve de présider aux destinées du pays est de plus en plus brisé si on sait que les chances pour que Alassane Ouattara lui accorde l’amnistie sont très réduites. Pendant ce temps, la cour d’appel a confirméle 15 janvier dernier la condamnation à deux ans de prison ferme de deux de ses lieutenants. Il s’agit de deux cadres de son mouvement, Générations et peuples solidaires (GPS) arrêtés pour « maintien illégal d’un parti politique » et « atteinte à l’ordre public ».

Parallèlement, le cas de Laurent Gbagbo a également attiré l’attention de l’opinion publique. Il a été gracié par l’autorité publique, ce qui n’efface pas les lourdes charges qui pèsent sur lui, l’empêchant ainsi d’être réintégré sur listes électorales. Le même sort est réservé à Charles Blé Goudé qui a toujours l’épée de Damoclès de Dame Justice sur sa tête, l'empêchant de participer à la prochaine présidentielle. Également, le duel fratricide des héritiers d'Houphouët est toujours à l’ordre du jour. En effet, Billon maintient toujours sa candidature “rebelle” contre la décision du parti d’investir l’homme d’affaires Tidjane Thiam. Pour régler ces lancinants problèmes autour de l’enjeu électoral, des voix s’élèvent pour réclamer un dialogue entre les parties prenantes. De son côté, le gouvernement semble ne pas adhérer à cette proposition puisque selon les autorités, toutes ces questions ont déjà été débattues lors des précédents dialogues nationaux. Le 8 janvier dernier, leporte-parole du gouvernement a tenu à préciser que les éditions précédentes “ont permis de passer en revue toutes les préoccupations”.

Au registre diplomatique, les tensions diplomatiques avec le Burkina Faso continuent toujours de défrayer la chronique. Les diplomates rappelés par le capitaine Traoré ont finalement quitté Abidjan, ce qui aggrave davantage la situation. Cet acte fort posé par les dirigeants des deux pays, complexifie davantage leurs relations bilatérales. Pour rappel, ces conflits ont toujours existé entre ces deux Etats du temps d'Houphouët et Sankara.

Sous un autre registre, le début de l’année 2025 marque un tournant décisif dans la coopération sécuritaire entre Paris et Abidjan. Comment analyser cette situation si on sait que la Côte d’Ivoire était jadis un allié sûr de l’ancien colonisateur ? Il est à noter que les français ne partent pas complètement de la Côte d’Ivoire vu que la France envisage non pas un retrait total mais une réduction de sa présence armée, faisant passer le nombre de soldats dans le pays de 2.200 à 600 dans le cadre de ce qu’elle appelle le “redéploiement” de son dispositif militaire.

Source : Météo Sahel Janvier 2025

Télécharger l'intégralité de la Météo Sahel

Paul Biya sera-t-il candidat à la présidentielle d’octobre 2025 ? Au Cameroun, le brouillard autour de cette interrogation reste intact, ravivant ainsi les débats au sein de l’opinion publique et de la classe politique. Cette fièvre s’est d’abord fait sentir dans la communauté catholique du pays. En effet, Monseigneur Kleda, archevêque de Douala, avait qualifié une possible candidature de Biya de pas « réaliste ». Puis par la suite, ses homologues de Ngaoundere et de Yagoua, dans l'Extrême-Nord, lui ont emboîté le pas. Ce faisant, les autorités ont dans la foulée, tenté de faire redescendre la fièvre. C’est visiblement la raison pour laquelle le ministre de l'Administration territoriale Paul Atanga Nji a rencontré le représentant du Vatican, Monseigneur José Avelino Bettencourt. Si le ministre a déclaré que les relations entre Yaoundé et le Vatican sont « excellentes », le ministre de la Communication René-Emmanuel Sadi a, lui, affirmé qu’ « il n'existe aucun conflit entre le gouvernement et les confessions religieuses. » Au terme de son séminaire annuel tenu le 11 janvier, la Conférence épiscopale nationale du Cameroun (Cenc) a dans un message, déploré « la crise économique et la situation particulièrement préoccupante du pays », dans lequel les Camerounais sont « contraints de vivre avec la corruption et de l’accepter comme une réalité quotidienne, renforçant ainsi ce fléau. » Dans un communiqué de presse tenu le 9 janvier, l’opposant Maurice Kanto a une fois de plus vivement fustigé le processus électoral. Selon lui, les irrégularités de l’Elecam (l’organisme en charge des élections) qu’il dénonce, constituent un « manquement grave à la loi est de nature à compromettre la participation de nombreux Camerounais au scrutin présidentiel attendu. »

De son côté, le RDPC (Rassemblement démocratique du peuple camerounais) s’est rapidement mis en cheval de bataille. Le parti au pouvoir a sans surprise dénoncé ce qu’il considère comme une campagne de « discrédit du gouvernement » et de « dénigrement » à l’endroit de son « candidat naturel » : Paul Biya. Parallèlement, le Conseil des chefs traditionnels au Cameroun – regroupant trois cents autorités traditionnelles du pays – a, au terme d’un congrès le 27 janvier, formulé son « soutien ferme et définitif » à la candidature de Biya. Plus tôt dans le mois, le 10 janvier, le président Biya et Toïmano Ndam Njoya, présidente de l'UDC (parti politique d'opposition) se sont entretenus au palais présidentiel, au sujet de la présidentielle. « Nous avons pu porter à la haute attention du président (…) la grande préoccupation de l'heure des principaux acteurs du processus électorale, à savoir un système électoral accepté, partagé par tous, garant du jeu démocratique, crédible, juste, équitable, transparent et pacifique », a-t-elle indiqué, au terme de l’échange.

Temps difficiles pour les défenseurs des droits humains

Dans la nuit du 18 au 19 janvier, les locaux de l'ONG Nouveaux droits de l'homme – très active dans la défense des droits de l'homme - ont été cambriolés. Unités centrales de tous les postes d'ordinateurs, des disques durs et des clés USB ont été emportées par les cambrioleurs. « Cela crée une situation de traumatisme. Depuis des mois, nous sommes confrontés à une recrudescence de menaces et d’intimidations en raison de nos prises de position sur les libertés publiques au Cameroun », a déploré la directrice, Cyrille Rolande Bechon.

Quelques jours avant, c’était la convocation le 14 janvier de la présidente du Conseil d'administration du Réseau des défenseurs des droits humains d'Afrique centrale (Redhac), maître Alice Nkom à la gendarmerie nationale, qui faisait polémique. En effet, la figure de la société civile connue pour son combat pour les droits des personnes LGBT est visée par une dénonciation de l’ONG Observatoire du développement sociétal (ODS) pour « atteinte à sûreté de l'État » et « financement du terrorisme ». Ceci, en raison d’un forum sur la paix et la transition organisé et auquel elle a participé il y a cinq ans en Allemagne. Dans une lettre adressée au commissaire du gouvernement du tribunal militaire de Yaoundé, deux avocats ont estimé que ces accusations étaient « fantaisistes ».

Enfin, une semaine après avoir été remis au président Emmanuel Macron, le rapport de la commission sur le rôle de la France dans la répression des mouvements indépendantistes au Cameroun, a été également remis le 28 janvier, au président Paul Biya. Pendant deux ans, quatorze chercheurs (historiens français et camerounais) ont travaillé à débroussailler l’histoire de cette période sombre et enfouie de l’histoire franco-camerounaise. Les conclusions du rapportde 1000 pages sont limpides : la France a bel et bien mené de 1945 à 1971, une sanglante guerre contre les indépendantistes camerounais, autrefois opposés à l’ex empire colonial.

Source : Sahel weather January 2025

Download the full Sahel weather report

Will Paul Biya be a presidential candidate in October 2025? In Cameroon, the fog surrounding this question remains intact, rekindling debate within public opinion and the political class. This fever was first felt in the country's Catholic community. Indeed, Monseigneur Kleda, Archbishop of Douala, described Biya's possible candidacy as "unrealistic". His counterparts in Ngaoundere and Yagoua, in the Far North, followed suit. In the process, the authorities tried to bring the fever down. This is clearly why Minister of Territorial Administration Paul Atanga Nji met with the Vatican representative, Monsignor José Avelino Bettencourt. While the minister declared that relations between Yaoundé and the Vatican are "excellent", Communication Minister René-Emmanuel Sadi asserted that "there is no conflict between the government and religious denominations." At the end of its annual seminar held on January 11, the Cameroon National Episcopal Conference (Cenc) deplored in a message "the economic crisis and the particularly worrying situation in the country", in which Cameroonians are "forced to live with corruption and accept it as a daily reality, thus reinforcing this scourge." In a press release issued on January 9, opposition politician Maurice Kanto once again strongly criticized the electoral process. According to him, the irregularities of Elecam (the body in charge of elections) that he denounces, constitute a "serious breach of the law is likely to compromise the participation of many Cameroonians in the expected presidential election."

For its part, the RDPC (Rassemblement démocratique du peuple camerounais - Cameroon People's Democratic Rally) was quick to jump on the bandwagon. Unsurprisingly, the ruling party denounced what it saw as a campaign to "discredit the government" and "denigrate" its "natural candidate", Paul Biya. At the same time, the Council of Traditional Leaders in Cameroon - comprising three hundred of the country's traditional authorities - expressed its "firm and definitive support" for Biya's candidacy at the end of a congress on January 27. Earlier in the month, on January 10, President Biya and Toïmano Ndam Njoya, president of the UDC opposition party, met at the presidential palace to discuss the presidential election. "We were able to bring to the President's attention (...) the major current concern of the main players in the electoral process, namely an electoral system that is accepted, shared by all, a guarantor of the democratic game, credible, fair, equitable, transparent and peaceful", she said at the end of the exchange.

Hard times for human rights defenders

During the night of January 18 to 19, the premises of the NGO Nouveaux droits de l'homme - very active in the defense of human rights - were broken into. All computer workstations, hard drives and USB sticks were taken by the burglars. "This is creating a traumatic situation. For months now, we've been facing an upsurge in threats and intimidation because of our stance on civil liberties in Cameroon", lamented director Cyrille Rolande Bechon.

A few days earlier, the January 14th summons of the Chairwoman of the Board of Directors of the Central African Human Rights Defenders Network (Redhac), Maître Alice Nkom, to the national gendarmerie caused controversy. Indeed, the civil society figure known for her fight for the rights of LGBT people is the target of a denunciation by the NGO Observatoire du développement sociétal (ODS) for "undermining state security" and "financing terrorism". This is because of a forum on peace and transition organized and attended five years ago in Germany. In a letter addressed to the government commissioner of the Yaoundé military court, two lawyers described the charges as "fanciful".

Finally, a week after being handed over to President Emmanuel Macron, the commission's report on France's role in the repression of independence movements in Cameroon was also presented to President Paul Biya on January 28. For two years, fourteen researchers (French and Cameroonian historians) worked to unravel the history of this dark, buried period in Franco-Cameroonian history. The conclusions of the report 1,000-page are crystal-clear: from 1945 to 1971, France did indeed wage a bloody war against Cameroon's independence fighters, once opposed to the former colonial empire.

Source : Sahel weather January 2025

Download the full Sahel weather report

A few hours after the visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, heavy gunfire was heard on the evening of January 8 in the center of N'Djamena, near the presidency. Some twenty assailants attempted to attack the presidential compound in the Djambel Bahr district. According to government spokesman Abderaman Koulamalla, the attack was an "attempt to destabilize (...) young people from a district of Ndjamena and from a Chadian community".

Ruling out the possibility of terrorism, he tried to put the incident into perspective. "On the face of it, it has nothing to do with Boko Haram (...) If there were no deaths, it would make you smile, because it's a bunch of nickel-and-diming gangs who came with wire cutters, knives, no weapons of war", he asserted. He continued: "There's nothing to panic about. There's no threat to the security of our country (...) It's really an epiphenomenon that we'll soon forget." Reacting to the incident, President Mahamat Idriss Déby said that "the assailants in this vain attempt were aiming to vitrify [him]." According to the government, the attack left 20 dead: 18 of the assailants and two soldiers. An investigation into the incident has been entrusted to the public prosecutor.

France out, Turkey in?

Meanwhile, January saw the end of a century-long French military presence in Chad. On January 11, the military base in Abéché - the country's third most populous city - was officially handed back by France. Just over two weeks later, on January 30, the Adji Kosseï base in Ndjamena was handed over. The last 180 soldiers left Chadian soil on the same day. It was on the runway of this base that Chad celebrated the official end of the French military presence in the country the following morning. Another sign of the divorce between France and Chad was the reaction of the Chadian President, who described the remarks made by French President Emmanuel Macron as "remarks bordering on contempt for Africa and Africans". Macron had lamented the "ingratitude" of African heads of state, who he claimed had "forgotten" to "say thank you" when France intervened militarily in the Sahel in 2013.

At the same time, RFI reports, Turkish drones will be installed at the Faya-Largeau base in the north of the country, where Turkey already has a presence, and probably soon at the Abeche base. This is not, however, a full-scale military presence, as the source points out, "but rather technicians, specialists in charge of operating the Bayraktar aerial drones acquired by Chad. The personnel deployed in Faya-Largeau are therefore drone pilots or Bayraktar employees.

Déby, the country's leader more than ever?

Unsurprisingly, the ruling party won the legislative elections held on December 29, 2024, which were boycotted by part of the opposition. The Mouvement patriotique du salut (MPS) won an absolute majority of seats in the new National Assembly: 124 out of a total of 188. A week after the publication of these results by the Constitutional Court, President Déby was appointed national president of the ruling party on January 30, at the 13th MPS congress. Until then, he had only been honorary president. On the eve of this distinction, the opposition Succès Masra said he was ready to work with President Déby. "We are ready to work with the President of the Republic, Marshal Mahamat Idriss Déby, to bring the added value of our political force to this meeting, which is a republican meeting in the service of the Chadian people", he declared. A curious call, to say the least, given that the former Prime Minister's party boycotted the recent legislative elections.

Source : Météo Sahel Janvier 2025

Télécharger l'intégralité de la Météo Sahel

Quelques heures après la visite du ministre chinois des Affaires étrangères Wang Yi, des tirs nourris ont été entendus dans la soirée du 8 janvier dans le centre de N’Djamena, près de la présidence. A l’origine de cette frayeur, une vingtaine d'assaillants qui ont tenté d’attaquer la cité présidentielle, sise dans le quartier Djambel Bahr. Selon le porte-parole du gouvernement Abderaman Koulamalla, il s’agit d’une « tentative de déstabilisation (…) de jeunes qui viennent d'un quartier de Ndjamena et qui sont issus d'une communauté tchadienne. »

Ecartant de suite la piste terroriste, il s’est efforcé de relativiser l’importance de l’incident. « À première vue, ça n'a rien à voir avec Boko Haram (…) S'il n'y avait pas de morts, ça prêterait à sourire parce que c'est un ramassis de bandes de nickelés qui sont venues avec des coupes-coupes, des couteaux, aucune arme de guerre », a-t-il affirmé. Avant de poursuivre : « Il n'y a pas de quoi paniquer, il n'y a rien. Il n'y a aucune menace sur la sécurité de notre pays (…) C'est vraiment un épiphénomène qu'on va très vite oublier. » Réagissant à l’incident, le président Mahamat Idriss Déby a indiqué que « les assaillants de cette vaine tentative visaient à [le] vitrifier. » Selon le gouvernement, le bilan de l’attaque est de 20 morts : 18 parmi les assaillants et deux militaires. Une enquête pour éclaircir l’incident a été confiée au procureur de la République.

France out, Turquie in ?

Pendant ce temps, le mois de janvier a été un clap de fin d’une présence militaire française de plus d’un siècle au Tchad. En effet, le 11 janvier, la base militaire d'Abéché – troisième ville la plus peuplée du pays – a été officiellement rétrocédée par la France. Un peu plus de deux semaines plus tard, le 30 janvier, ce fut au tour de la base d’Adji Kosseï à Ndjamena, d’être rétrocédée. Les 180 derniers militaires, ont quitté le sol tchadien dans la même journée. C’est d’ailleurs sur la piste de l’aéroport de cette base que le Tchad a célébré le lendemain au matin, la fin officielle de la présence militaire française dans le pays. Un autre signe du divorce entre la France et le Tchad, la réaction du président tchadien qui a qualifié de « propos qui frisent le mépris envers l’Afrique et les Africains », des propos du président français Emmanuel Macron. En effet, ce dernier avait regretté « l’ingratitude » des chefs d’Etat africains, qui, selon lui, auraient « oublié » de « dire merci » lorsque la France était intervenue militairement au Sahel, en 2013.

Parallèlement, renseigne RFI, des drones turcs vont être installés sur la base de Faya-Largeau (nord du pays), où la Turquie était déjà présente, et probablement bientôt dans la base d’Abéché. Il ne s’agit toutefois pas d’une présence militaire en bonne et due forme tempère la source, notifiant que « ce sont plutôt des techniciens qui y sont, des spécialistes chargés de mettre en œuvre les drones aériens Bayraktar acquis par le Tchad. Les personnels déployés à Faya-Largeau sont donc des pilotes de drones ou encore des employés de Bayraktar. »

Déby, plus que jamais chef du pays ?

Sans surprise, le parti au pouvoir a largement remporté les élections législatives du scrutin du 29 décembre 2024, boycottées par une partie de l’opposition. Le Mouvement patriotique du salut (MPS) obtient ainsi la majorité absolue des sièges dans la nouvelle Assemblée nationale : 124 sur 188 au total. Une semaine après la publication de ces résultats par la Cour constitutionnelle, le président Déby a été désigné le 30 janvier, président national du parti au pouvoir, lors du 13ème congrès du MPS. Jusque-là, il n’en était que le président d’honneur. La veille de cette distinction, l’opposant Succès Masra s’est dit prêt à travailler avec le président Déby. « Nous sommes prêts à œuvrer avec le président de la République, le maréchal Mahamat Idriss Déby, pour apporter avec tous autour de la table la valeur ajoutée de notre force politique à ce rendez-vous, qui est un rendez-vous républicain au service du peuple tchadien », a-t-il déclaré. Un appel du pied pour le moins curieux, étant donné que le parti de l’ex premier ministre avait boycotté les récentes élections législatives.